At Veterinarians Without Borders North America (VWB), our team members and volunteers are often on the frontlines of building capacity for animal health through trainings and other veterinary services aimed at keeping animals and communities as healthy as possible. Because of this incredible and varied community of voices, VWB has launched 'Ask an Expert' — a blog dedicated to featuring community members and their varying experiences in the animal health space.

In this edition of Ask an Expert, we connected with Dr. Naima Jutha, Wildlife Veterinarian and Chief Veterinary Officer for the Government of the Northwest Territories. Based in Yellowknife, Dr. Jutha leads the Wildlife Health Program within the Department of Environment and Climate Change, monitoring and responding to emerging health threats among northern wildlife populations.

In our conversation, Veterinarians Without Borders (VWB) explored how her work reflects the core of the One Health approach—recognizing that the health of wildlife, people, and pets are deeply interconnected. From tracking rabies in wildlife populations to monitoring the effects of climate change on animal health, Dr. Jutha shared how northern communities, hunters, and trappers play a vital role in early detection and disease prevention. She also discussed the growing importance of combining traditional knowledge with science to build resilient, community-led systems that protect both wildlife and people across Canada’s North.

"I think my biggest hope is the strength of the North and northern communities. I see it firsthand every moment we get to work together. We're combining science with local knowledge and applying co-monitoring and co-management strategies. We're building these strong and meaningful partnerships with people and communities that truly care about the wildlife, about their health and the health of animals and people for generations to come."

Dr. Jutha examines a tranquilized grizzly bear that has been translocated to the tundra for human-wildlife conflict management purposes.

Dr. Jutha examines a tranquilized grizzly bear that has been translocated to the tundra for human-wildlife conflict management purposes.

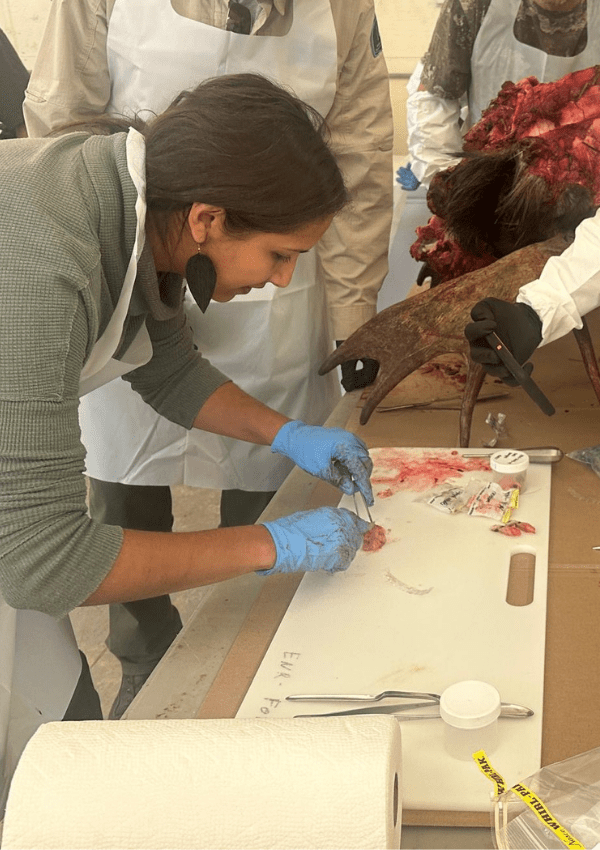

Dr. Jutha works with Indigenous guardians, community harvesters, and wildlife officers to train in sample collection methods as part of a community-based Chronic Wasting Disease monitoring program.

Dr. Jutha works with Indigenous guardians, community harvesters, and wildlife officers to train in sample collection methods as part of a community-based Chronic Wasting Disease monitoring program.

Q: Can you talk about your role as the wildlife veterinarian for the Northwest Territories?

A: Since September 2020, I've served as the wildlife veterinarian and Chief Veterinary Officer for the Northwest Territories. I work under the Government of the Northwest Territories’ Department of Environment and Climate Change. Largely, my job is to keep a close eye on the health of our wildlife populations, which means we investigate unusual events, for example, and also coordinate programs that track diseases and health status in animals.

And, as part of my position, I run what we call the "ECC Wildlife Health Program". I really think the role of this program is kind of a dual focus. You're safeguarding and understanding the health of wildlife populations, which are obviously quite a big part of life in the North for many people and communities. While doing so, you're also protecting people, pets, and communities through that work.

Q: Why is keeping wildlife healthy so important for the health of people and pets in the North?

A: That's a really good question. In the North, people rely on wildlife for food and also their culture and their livelihoods, generally. When animals are healthy or they're resilient to health threats, then it means safer food, fewer risks of disease spillover, and healthier ecosystems overall. But, if wildlife get sick, or if they are exposed to new health threats that they're not prepared for, it can certainly affect people, pets, and entire communities. The spillover of diseases may impact them directly or may affect the abundance or resilience of wildlife.

Q: What kinds of diseases can pass from animals to people, and how do you keep an eye out for them?

A: There are diseases that we see in the North, or that we monitor for in the North, and haven’t seen yet. These diseases could pass from animals to people, and some of them can be passed through their pets. I would say rabies is probably one of the best-known diseases in the North. This poses a real life-threatening risk to people and to pets if they're bitten. In addition to rabies, we watch for other zoonotic diseases like avian influenza in birds, anthrax in bison, and brucella in muskoxen. There are parasites, too, like trichinella or echinococcus, that we monitor in bears and other carnivores. I think all of these are very important and they get a lot of attention and perhaps also need a lot of that attention in the North.

We have rabies in our Arctic fox population; it's often in our red fox population, too, at least where they overlap with Arctic foxes. Many communities in the North lack basic access to veterinary care on a regular basis and, therefore, we don't have the privilege of having well-vaccinated dog populations that we might see in the South. So, this kind of creates the perfect “One Health storm”, where we worry about this disease potentially spilling over into dogs and potentially, worst case scenario, into people. I think that it's a very clear example of why it's so important to monitor wildlife health and track when rabies might be an issue, along with other diseases.

I also have the great privilege of working with communities, hunters, trappers, and biologists to collect samples, and – especially when we investigate animals that are found sick or are behaving strangely – I think it's all really critical to monitor these diseases that could spillover and create real problems for people, pets, and wildlife populations. And, whether it's rabies or other diseases, we also partner with different labs and universities to test samples that we collect opportunistically so we can spot trends or detect emerging concerns early. It really is a group effort.

Q: Are there any emerging diseases you’re particularly worried about?

A: The climate is changing; the landscape is changing. And, because of this, we're seeing shifts in things like insect-borne diseases and parasites, like ticks, creeping further north in our moose and even caribou, for example. We've started seeing increasing impacts more recently of filarioids, which are parasites transmitted by mosquitoes or biting flies that can affect our ungulates. … West Nile virus in birds and mosquitoes… White nose syndrome in bats... Chronic Wasting Disease in cervids… Many of these concerns may be creeping closer to our border as the climate warms.

Just bringing it back to the rabies story: we see Arctic foxes changing their behaviours and ranges based on when sea ice is freezing up or breaking apart. People have told us that they’re seeing red foxes and Arctic foxes overlap more, too. Rabies is a climate-sensitive zoonosis; it's frequency and cycles may change with climate change, and we need to be prepared for that.

An Arctic fox on the snowy tundra

An Arctic fox on the snowy tundra

Muskoxen forage in the North

Muskoxen forage in the North

A black bear searches for food

A black bear searches for food

Q: How do local hunters, trappers and other community members help with monitoring wildlife, and how does traditional knowledge play a role?

A: Hunters, trappers, and other members of local communities are absolutely essential in terms of monitoring wildlife health. They’re the ones with actual boots on the ground and are often noticing changes long before we can detect them in our data. For example, I may have harvesters call me to say, “this year we're noticing there's less fat on the caribou we're hunting”, and noting that change in body condition might be a good indicator that there's something caribou are coping with.

This kind of local knowledge is a really powerful early warning system and it guides the questions that we are all going to collectively ask and hopefully endeavour to answer.

It's cool being a veterinarian in the wildlife field. And difficult, of course, in a lot of ways because we don't have people bringing that caribou, for example, into a clinic on a leash to say, “this animal has been coughing”… You rely so much on people's land-based observations. Things like “we had to travel further this year to find a moose that was suitable for hunting” or “when I cut my caribou, there was less fat around the kidney than I'm used to, so it was kind of sticky to take out”. Well, what does all that mean? We rely so much on traditional and observational knowledge. It’s ways of knowing and living with wildlife that have these deep, long-standing cultural or spiritual connections to animals that we're all monitoring. And, people can compare what they're seeing now to maybe what their grandparents or their parents told them that they observed over decades or longer.

Q: What simple steps can communities take to stay safe while continuing to rely on wildlife for food and culture?

A: Keeping your pets vaccinated against preventable diseases is one way. And I think, you know, keeping your pets healthy so that they're resilient to diseases can help when we're considering those pets as the connection to human health. As a general rule, it's a good idea for people to avoid handling sick, unusually tame, or abnormally acting wildlife, or wildlife that they've found dead. If you do see something unusual like that, or you’re worried that an animal has a disease, you can report that to your local Department of Environment and Climate Change Wildlife Office. Our officers are there as a critical resource, and we're able to assess and provide feedback if there's an animal that may have interacted with your pet or with a member of your family or yourself. The good news is that wildlife in the NWT, generally, are healthy, and people up here really do know what to look out for to recognize when an animal might be showing signs of illness. When people are butchering or skinning animals, they can wear gloves and work in well ventilated areas if they’re worried about sick animals. If people are seeing evidence of wildlife disease, take lots of pictures and, if people are comfortable, take samples of the abnormal thing, which they can submit to their local ECC office and we will investigate. I'm always interested in working together with people and communities in NWT to monitor and learn more about the health of our wildlife and the diseases that impact them. People can reach out to my email directly anytime at wildlifeveterinarian@gov.nt.ca with any wildlife-related questions or concerns.

Q: Looking ahead, what’s the biggest challenge — and the biggest hope — you have for wildlife and community health in the North?

A: I think the biggest challenge we face is the sheer scale of the North. It's this huge, vast landscape and we have very limited resources to monitor every corner of it. Also, one thing we spoke about before, are the effects of climate change. We're seeing them faster than most other places on the planet. Up North, these effects are things that people are actually observing year after year. Shorelines are changing, the sea ice is breaking up or freezing at different times of year, and we're seeing wildfires at scales that I didn't know was possible when I was growing up. What all this means to me is that we've got to move fast despite these challenges. And we've got to figure out how it's going to affect animals and, therefore, our people, and our pets.

On the flip side, I think my biggest hope is the strength of the North and northern communities. I see it firsthand every moment we get to work together. We're combining science with local knowledge and applying co-monitoring and co-management strategies. We're building these strong and meaningful partnerships with people and communities that truly care about the wildlife, about their health, and the health of animals and people for generations to come. I think we can promote the health of our wildlife and our landscapes and protect wildlife and people for a very long time because people in the North are strong and they're willing and wildlife is still very important to everyone up here.

>>Learn more about VWB's work to support animals and communities in Canada's remote North.<<