Written by Tanja Kisslinger, Director of Communications, VWB. Special thanks to Dr. Andrea Ellis, DVM—Public Health and One Health Consultant, and VWB Board Member—for reviewing and providing expert insights for this article.

World Zoonoses Day, observed annually on July 6th, serves as a critical reminder of the inextricable link between human and animal health. It is a day to reflect not only on high-profile emerging threats, but also on the persistent and often overlooked zoonotic diseases that continue to endanger lives and livelihoods around the world.

Among these is anthrax—a centuries-old bacterial infection primarily affecting herbivores that continues to re-emerge in endemic regions. Despite being both preventable and treatable, anthrax remains a potent threat, particularly in rural and resource-limited settings. Anthrax spores can survive in soil for decades and resurface due to flooding, drought, or land disturbance. Herbivores become infected by ingesting spores in the soil or feed, while carnivores become infected by eating meat from infected animals, and biting flies appear to further the spread. Its ability to cause rapid, severe illness and death in animals, with the potential for transmission to humans, underscores the need for continued vigilance, strengthened surveillance, and a coordinated, multisectoral response.

This blog explores the enduring threat of anthrax, the factors driving its persistence, and the growing recognition that a community-led, One Health approach is vital for its control.

Figure: Why Anthrax Surveillance Still Matters

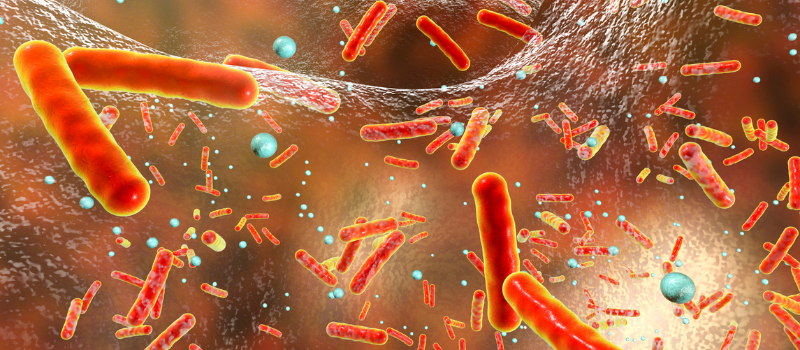

Anthrax: A Zoonotic Threat in Three Forms

Bacillus anthracis, the bacterium that causes anthrax, forms highly durable spores capable of surviving in soil for decades. This environmental persistence makes eradication challenging and positions anthrax as a continual threat in many parts of the world.

Humans may contract anthrax through three primary routes:

- Cutaneous Anthrax: The most common form, occurring when spores enter the body through cuts or abrasions. Often linked to handling infected animals or contaminated animal products, it presents as a painless sore that becomes a necrotic ulcer (eschar). With timely antibiotic treatment, recovery is likely.

- Inhalational Anthrax: The most severe form, contracted through inhalation of spores. Symptoms begin as mild respiratory illness and can progress rapidly to shock and death. It is rare but carries a high mortality rate even with treatment. Bacillus anthracis has also been developed and used as a biological weapon when delivered as an inhalant.

- Gastrointestinal Anthrax: Contracted through ingestion of contaminated meat. It causes vomiting, abdominal pain, and bloody diarrhea, and can be fatal without prompt treatment.

In countries with strong veterinary and public health systems, human cases are rare. But in many regions where livestock vaccination is sporadic and surveillance is weak, anthrax remains an ever-present danger—both for animals and the people who depend on them.

Why Does Anthrax Keep Coming Back?

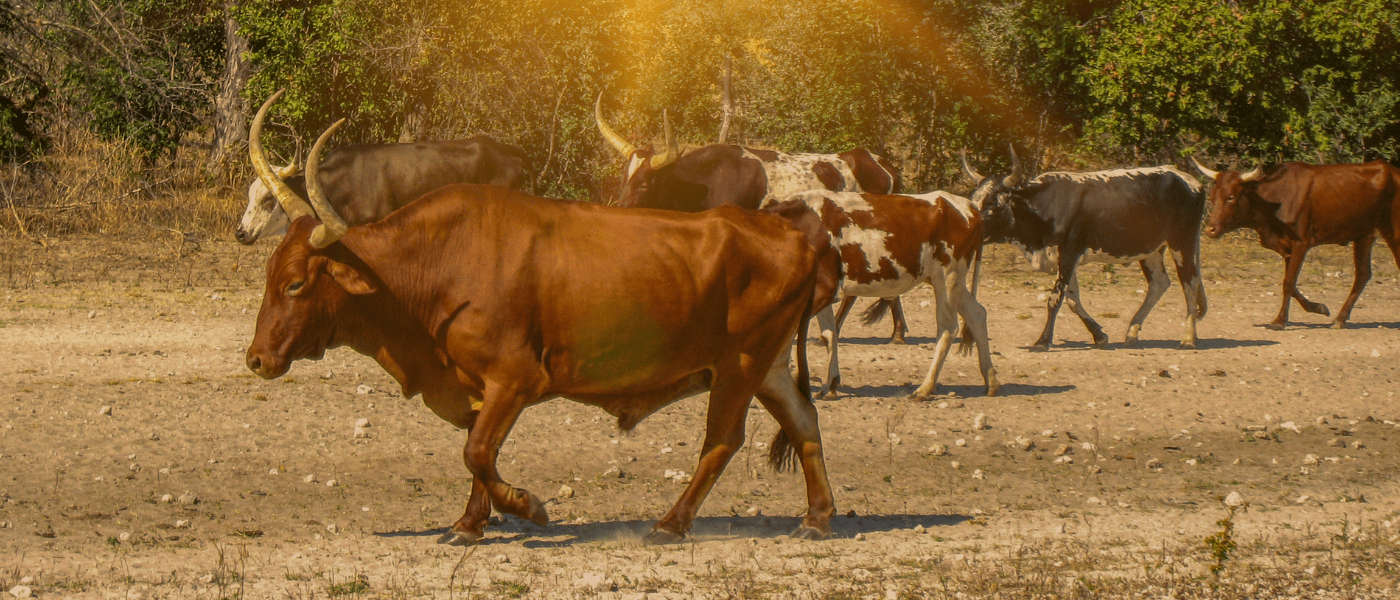

PHOTO: Livestock grazing in dry, dusty conditions are at greater risk of ingesting anthrax spores that resurface in the soil during droughts or environmental disturbance.

PHOTO: Livestock grazing in dry, dusty conditions are at greater risk of ingesting anthrax spores that resurface in the soil during droughts or environmental disturbance.

Anthrax’s continued re-emergence in endemic regions stems from a complex interplay of biological, environmental, and socio-economic factors:

- Gaps in Livestock Vaccination: While livestock vaccination is highly effective in preventing anthrax outbreaks, many regions lack consistent access due to logistical, financial, or informational barriers.

- Underreporting and Weak Surveillance: In many remote areas, anthrax cases go unreported due to limited health infrastructure, diagnostic capacity, or fear of stigma—undermining outbreak detection and response.

- Traditional Practices and Cultural Norms: Practices like slaughtering or consuming sick or dead animals—especially in the absence of veterinary guidance—can inadvertently fuel disease transmission.

- Climate Change: Shifting weather patterns exacerbate anthrax risks. Droughts concentrate animals around water sources, while floods can disseminate spores across grazing lands, increasing exposure.

Community-Based Surveillance: The Front Line of Early Detection

Given the limitations of centralized disease surveillance systems, community-based surveillance (CBS) is increasingly recognized as a vital tool in the fight against anthrax. CBS harnesses the proximity, knowledge, and trust of local actors to improve detection, reporting, and response at the grassroots level.

PHOTO: A Community Animal Health Worker in Ghana, trained through VWB’s VETS program, records livestock and farmer information during a vaccination campaign—supporting disease surveillance and early detection in rural communities..

PHOTO: A Community Animal Health Worker in Ghana, trained through VWB’s VETS program, records livestock and farmer information during a vaccination campaign—supporting disease surveillance and early detection in rural communities..

Key components include:

- Training and Empowering Community Health Workers (CHWs) and Community Animal Health Workers (CAHWs) to recognize clinical signs of anthrax in both humans and animals, collect and transport samples, and promote health education.

- Establishing Farmer Networks and Local One Health Champions to report unusual livestock deaths or symptoms. These actors often serve as the first observers of emerging health threats.

- Training Community Members in Safe Carcass Management to ensure they avoid opening suspected carcasses and report them for safe disposal—typically through incineration or deep burial with lime—to prevent spore formation and further environmental contamination.

- Using Mobile Technology and Digital Tools to improve the speed and accuracy of reporting, connect community members to professionals, and share critical outbreak alerts.

- Building Trust and Addressing Stigma, which is essential for ensuring communities are willing to report cases and seek care. Education campaigns that dispel myths and promote safe practices are critical.

How VWB Is Making an Impact: The COHERS Program in Rwanda and Senegal

Veterinarians Without Borders (VWB) is confronting the persistent challenge of anthrax and other neglected zoonoses through its Community One Health Empowerment for Resilience and Sustainability (COHERS) program, active in Rwanda’s Nyamagabe District and in the Kedougou and Velingara Departments of Senegal.

These regions are characterized by high levels of human-animal-environment interaction—ideal conditions for the transmission of zoonotic diseases like anthrax, cysticercosis, and brucellosis. COHERS specifically targets vulnerable and marginalized populations, particularly women and girls, who are often responsible for livestock care, water management, and food preparation—roles that heighten exposure to zoonotic pathogens.

PHOTO: In Rwanda, VWB’s COHERS partners conduct a hands-on livestock health training with local farmers—part of broader efforts to improve community-based surveillance and early detection of zoonotic disease.

PHOTO: In Rwanda, VWB’s COHERS partners conduct a hands-on livestock health training with local farmers—part of broader efforts to improve community-based surveillance and early detection of zoonotic disease.

At the heart of COHERS is a gender-responsive, community-based approach to disease prevention and early detection. The program is:

- Establishing and training One Health Teams (OHTs)—multidisciplinary groups composed of Community Health Workers (CHWs), Community Animal Health Workers (CAHWs), and Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) specialists—who collaborate to identify, prevent, and respond to zoonotic disease risks at the local level.

- Strengthening anthrax surveillance and outbreak response by equipping CAHWs with training and tools to recognize and report unusual livestock deaths and symptoms consistent with anthrax. These frontline responders act as early warning systems, particularly in communities with limited access to veterinary infrastructure.

- Improving local awareness through targeted outreach and education, including One Health Days, sensitization campaigns, and participatory workshops. These efforts help demystify zoonotic diseases like anthrax and encourage safe animal handling, proper carcass disposal, and timely medical care.

- Promoting gender equity in animal and public health decision-making, ensuring that women are not only included in training sessions but also empowered to take leadership roles in surveillance, household sanitation, and livestock health management.

- Supporting evidence-based policy development and research, generating localized data to inform national One Health strategies and strengthen coordination between human, animal, and environmental health authorities.

Through COHERS, VWB aims to directly reach over 127,000 people by 2027, building lasting local capacity to manage zoonotic threats like anthrax before they escalate into full-scale crises.

The Human and Economic Cost of Inaction

Neglecting anthrax surveillance and control in animals and people carries steep consequences:

- Misdiagnosis and Delayed Treatment: Without accurate case detection and data, health systems cannot allocate resources effectively. Undiagnosed or misdiagnosed anthrax cases delay outbreak response and worsen outcomes.

- Stigma and Isolation: In affected communities, fear of being blamed or shunned can prevent people from reporting cases or seeking care—furthering disease spread.

- Livestock Losses and Economic Impact: In agrarian economies, anthrax outbreaks can devastate herds, cutting off primary sources of income, food, and trade for families.

- Food Insecurity: Beyond immediate losses, anthrax disrupts local food systems and markets, increasing vulnerability among already at-risk populations.

Toward Resilient Surveillance: A One Health Imperative

Effective anthrax control depends on embracing One Health—a collaborative, multisectoral approach that acknowledges the shared health of people, animals, and ecosystems.

Key strategies include:

- Joint Surveillance and Data Integration across animal and human health systems to enable early detection and more targeted interventions.

- Collaborative Risk Assessments that consider climate, land use, and socio-economic drivers of anthrax transmission.

- Integrated Response Protocols across veterinary, environmental, and public health sectors to ensure coordinated outbreak management.

- One Health Education and Training for field professionals and local communities to build shared understanding, reduce silos, and foster collective action.

Conclusion: Investing in Prevention, Building for the Future

Anthrax remains a clear example of why neglected zoonotic diseases must not be overlooked. Its prevention is not technologically complex—but it does require sustained investment, local engagement, and systems that reflect the realities of rural communities.

By strengthening surveillance through community-based approaches, investing in animal vaccination, and embedding these efforts in a broader One Health strategy, we can transform reactive crisis response into proactive, long-term resilience.

References:

- Dogonyaro, A., Wudu, B. M., Salihu, V. B., Kwaji, J., Garba, B., Barde, F. I., ... & Ahmed, A. S. (2023). Anthrax outbreak in a rural community in Nigeria: a case report. Pan African Medical Journal, 44(1), 1-5.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). (n.d.). Community-Based Surveillance (CBS). Retrieved from: https://cbs.ifrc.org/

- Ochwoto, G. O., Misinzo, G., Gura, Z., & Muturi, M. (2020). Anthrax in animals and humans in Kenya: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 14(4), e0008111.

- Pilo, P., Frey, J., Burnens, A. P., & Oevermann, A. (2015). Anthrax: a disease with historic, but also modern relevance. Swiss Medical Weekly, 145, w14194.

- World Health Organization. (2008). Anthrax in humans and animals. World Health Organization.

- World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). (n.d.). Anthrax. Retrieved from: https://www.woah.org/en/disease/anthrax/

Join us in strengthening community-based surveillance for zoonotic diseases like anthrax. Through One Health training, CAHW support, and programs like COHERS, VWB is helping communities detect outbreaks early and respond effectively. Donate, volunteer, or subscribe to advance early warning systems, safeguard lives and livelihoods, and build resilient animal health systems from the ground up.

Join us in strengthening community-based surveillance for zoonotic diseases like anthrax. Through One Health training, CAHW support, and programs like COHERS, VWB is helping communities detect outbreaks early and respond effectively. Donate, volunteer, or subscribe to advance early warning systems, safeguard lives and livelihoods, and build resilient animal health systems from the ground up.