In this edition of Ask an Expert, we spoke with Dave Shuey, a Veterinary Social Worker with IndeVets, about the growing field of veterinary social work and how innovative practice models can help bring balance, fulfilment, and sustainability back to veterinary medicine.

In this edition of Ask an Expert, we spoke with Dave Shuey, a Veterinary Social Worker with IndeVets, about the growing field of veterinary social work and how innovative practice models can help bring balance, fulfilment, and sustainability back to veterinary medicine.

Drawing on his experience working with thousands of veterinary professionals, Dave shared insights into how the IndeVets model combines flexibility and autonomy with stability and support—addressing the unique mental health and wellness challenges faced by veterinarians today.

From exploring the social determinants of health and the emotional toll of veterinary work, to practical strategies for integrating social work, data-driven wellness, and compassionate leadership into practice culture, this conversation highlights how organizations like IndeVets are reimagining what a healthy, resilient veterinary community can look like.

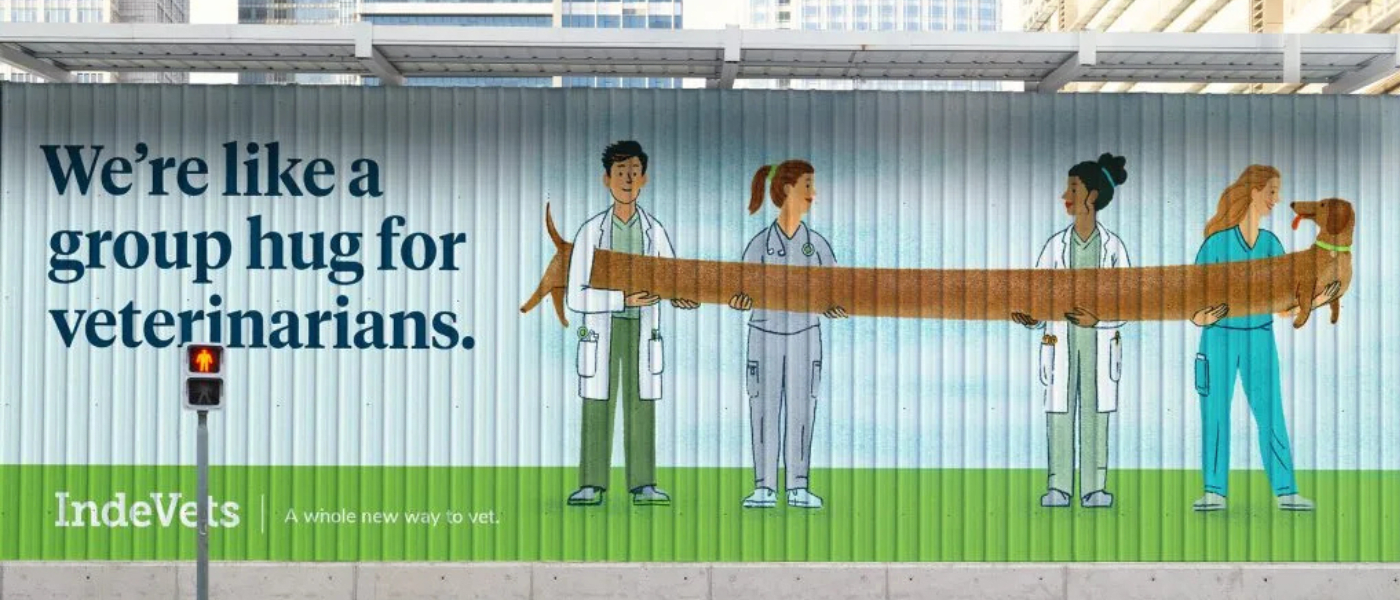

Q: Can you describe what makes IndeVets unique?

A: Our mission statement is that IndeVets was created to bring balance, fulfilment, and joy to veterinary medicine. IndeVets was founded by a practice manager who was looking for a better way, who became our CEO. They were joined by a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine who said there's got to be a way to give veterinarians some autonomy in their lives and some balance. They connected seven and a half years ago, and we are now a staffing organization.

Now, we've got over 200 doctors practicing nationwide in a ton of partner hospitals and the model is unique because there is a trend for relief work for veterinarians, which means lots of locum work and independent contractors. We blend the best of relief and associate roles—offering variety and flexibility, along with stability, benefits, and a dedicated support team.

We believe vets deserve the freedom to design their career around their life. It’s a new way to practice that prioritizes well-being, respects boundaries, and helps veterinarians rediscover the joy in vet med.

Q: How would you describe veterinary social work?

A: Veterinary social work is social work that's done at the intersection of the human-animal bond. In the United States especially, social workers are known as kind of the direct frontline mental health professionals – the people providing your therapy, your group work, and your behavioural health are mostly social workers. And, so when people say, “you're a social worker”, it's like, “you must be a therapist” or “you must be a mental health professional”.

But social work in general is so much more than that. It's addressing what we refer to as the social determinants of health. So, we look at where people are living, what their social networks are like, what their families are like, and what sort of things are happening where they are they live. Are they living around fresh food or are they living in an industrial area? Things like that.

If you take it to a veterinary perspective, veterinary social workers show up all over the place. The most common is maybe embedded in a veterinary hospital or a school of veterinary medicine where it would be the traditional mental health route, where a person could be caring for grief-stricken pet owner or navigating a really difficult diagnosis. But they also will help the providers, the staff, the technicians, and the doctors with the emotional toll that this work brings.

You'll also find veterinary social workers in the medical and emergency field, especially in cases of domestic violence. One of the pillars of veterinary social work is the link between human and animal violence. So, when you have domestic violence going on, animals are often caught in in the crosshairs.

Q: In your experience, what are the most common mental health or wellness challenges you see veterinarians, veterinary technologists, and/or clinic staff struggling with?

Q: In your experience, what are the most common mental health or wellness challenges you see veterinarians, veterinary technologists, and/or clinic staff struggling with?

A: I've talked to thousands of veterinary professionals at this point along with support staff and students. And I've seen almost everything. For me, the biggest mental health challenge is the failure to recognize the environmental and social drivers of the symptoms that we're trying to treat. Like, what are the conditions that breed burnout? What are the conditions that breed lack of capacity, fatigue, and all of that?

There are a few things that we notice. One is an unrelenting, physically hazardous environment in a veterinary setting. That's not only with teeth, claws, and sharp things, but also just the noise of the treatment area; things like ringing phones constantly. Or conditions that breed social isolation. There are a lot of veterinarians that when you ask them “who's in your social network or who is your support system?”… [they often don’t really have one]… because a lot of people around them simply can't handle their stories from work.

Another driver of burnout is the financial burden. A lot of young people are coming out of college with crushing financial debt. And, I would add to that, one of the leading causes of suicide attempts in veterinary medicine is cyberbullying; often from negative online reviews… you know, “this doctor charged me 800 bucks and ended up not being able to save my dog” or “these people are only in it for the money”.

Q: How can veterinary practices, including those working with models like IndeVets, integrate social work or wellness support in a practical way?

A: Coming into IndeVets, I wanted to make sure the model was practical. We have our headquarters in Philadelphia, but we're all over the U.S. and a lot of our work is done virtually. I think practice owners and managers are often data-driven and love numbers. We are data-driven in how we measure burnout and mental health. We gather all kinds of data on not only how people are doing with their emotional exhaustion and their emotional connection to people, patients, and their work, but also their sense of professional accomplishment.

We ask, “what's your workload like?”, “what's your sense of control?”, “what’s your sense of reward?” These things are quantifiable, and we use them as an instrument to track the level of burnout. We check every six months to see what people's journeys are like and what reflections the data is giving us. We consider what we can tweak and what tools we can use differently. You can't improve anything that you can't measure, and if we can get serious about being data-driven in something that has such an impact on the industry as health and wellness, I think that makes sense.

The second thing is to really pay attention to the physical environment that people are working in. What are the noise levels like? Are there windows? Are there places that people can get away? Also – smells! The olfactory sense physiologically has millions of connections to our limbic system, which is where our emotions live and where empathy lives. If we're in a room that smells really awful, it's been shown in study after study that people become less empathetic, intolerant, and less willing to help. So, taking a look at those physical environments is very important.

Also, actually honouring someone’s time off when they’re not at work is huge. It’s accepted far too often that veterinary staff are “on call” literally all the time. Often, these are people that have real trouble turning off their phones when they go home at night because they want to keep track of each case; for example, how a patient is doing. So, having the culture to say “we’re welcoming your time off but also enforcing it” by ensuring that they know the rest of the team can handle things.

Q: What role does organizational culture (leadership, communication, workload, boundaries) play in the mental health of veterinary staff, and how can a clinic begin to shift culture toward more resilience and support?

Q: What role does organizational culture (leadership, communication, workload, boundaries) play in the mental health of veterinary staff, and how can a clinic begin to shift culture toward more resilience and support?

A: There’s an old Hebrew saying that goes, “the fish rots from the head”. In other words: you can have all of the core values put on the walls, you can say all of the phrases, you can have all of the events and the programs, you can invest in all of this stuff – but if the leadership is not really walking in a vulnerable way – it’s not going to work. There is no healing it. If we're going to be data-driven and actually “walk the walk”, we have to maintain open feedback loops all the time.

On my e-mail signature, I have a quote from Mr. Rogers that says, “anything that is mentionable can be manageable”. So, if it’s not mentionable we can’t manage it. Things like suicidal ideation at work [something that is, sadly, prevalent in the veterinary community].

If leaders are vulnerable enough to talk about it, receive feedback, and put themselves in the way of what's happening, that’s going to be huge. So that's leadership, communication, workload, and boundaries at work. Any workload that does not allow for the normal necessary recovery processes that the body needs to do is an unmanageable workload and will lead to burnout.

Q: Can you share a scenario where veterinary social work made a measurable difference for a clinic or an individual professional?

A: There was a situation when Hurricane Helene blew through the southeastern United States with a clinic that, although making it through the storm, lost one of its staff members who took their own life. We were able to connect with the practice owner and hold space for what was going on in their life and connect them to as many resources as we could possibly find, not only for the staff, but for the family and community, too, [that had been through a lot].

Q: Anything else to add?

A: I always stress to veterinary audiences “you're not crazy”. You're not alone. There's nothing wrong with you. Look for the people that can sit with you and sit with your pain and try to become a person that can sit with someone else's pain, too.

Interested in finding more wellness resources focused on the veterinary community? Click here for more details.

You can also connect directly with IndeVets by calling 1-833-463-3838 or by completing this contact form.