Each year, Dog Bite Prevention Week serves as a reminder that understanding dog behaviour and responsible animal interactions aren’t just about safety—they're also vital for preventing the spread of zoonotic diseases like rabies. In remote communities across Alaska and northern Canada, where Veterinarians Without Borders North America (VWB) currently provides urgently needed care, the stakes are even higher. In these areas, access to veterinary care and emergency medical services can be limited, and free-roaming dog populations are more common, making dog bites more likely.

The numbers behind dog bites

A comprehensive study published in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (Gilchrist et al., 2008) found that approximately 4.5 million people in the United States are bitten by dogs each year, and one in five bites becomes infected. Children, particularly those between the ages of 5 and 9, are most at risk. While these statistics reflect national trends, they may be underestimated in remote and Indigenous communities, where bites are less frequently reported or documented.

In northern communities, including those in Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and rural Alaska, dog bites often go unrecorded but pose a significant health concern. These areas may have larger populations of free-roaming dogs, and when human health, veterinary, and animal control services are sparse or unavailable, the consequences of a bite—especially from an unvaccinated animal—can be serious.

The hidden risk: Rabies and zoonotic diseases

Dog bites are not only traumatic—they can also transmit zoonotic diseases, the most well-known being rabies. Rabies is a fatal viral disease that can be transmitted to humans through the bite or scratch of an infected animal. Once symptoms appear, rabies is almost always deadly.

Although Canada and the United States have reduced cases of rabies in dogs through widespread vaccination, the risk remains in wild and free-roaming animal populations, particularly in remote and underserved areas. Preventing dog bites, therefore, plays a critical role in protecting community health and reducing the risk of outbreaks.

Why dog bites happen

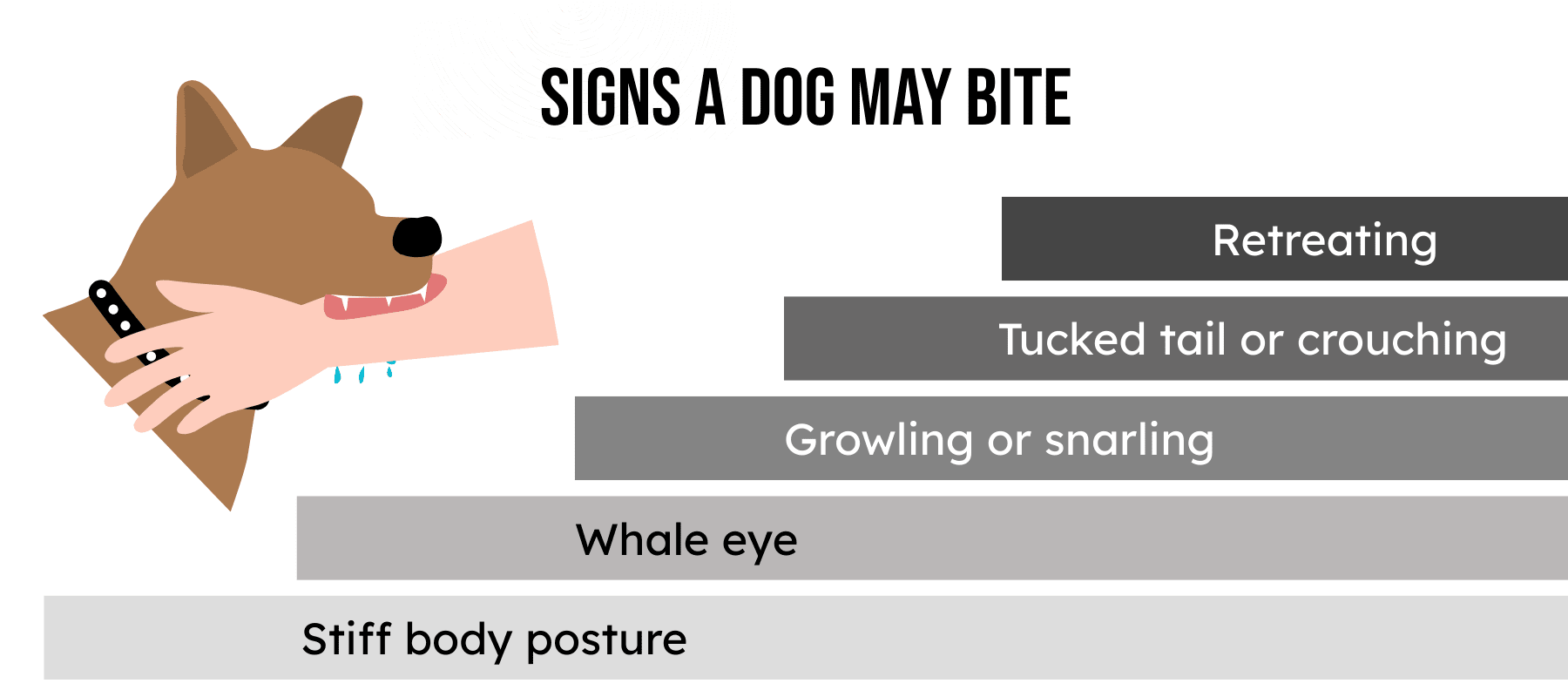

Dog bites often result from miscommunication between humans and dogs. Most dogs give warning signals before biting—these are typically body language cues that, when ignored or misunderstood, can lead to conflict. Common triggers include fear, pain, territorial behavior, or resource guarding.

Reading the signs: Body language that signals a dog may bite

Recognizing a dog’s body language can prevent countless injuries. Here are some key signs that a dog may feel threatened or uncomfortable:

- Stiff body posture: A dog holding its body rigid may be preparing to react defensively.

- Whale eye: When a dog shows the whites of its eyes, it's a sign of discomfort.

- Growling or snarling: Vocalizations are clear indicators to back off.

- Tucked tail or crouching: These are signs of fear, which can lead to defensive aggression.

- Avoiding eye contact or attempting to retreat: Dogs that try to move away should be given space.

Note that if a dog is infected with rabies, it may behave erratically—becoming aggressive, confused, or scared. Look for signs like foaming at the mouth, trouble swallowing, or stumbling.

Teaching children and adults in all communities—but especially in high-risk regions—how to interpret these signs is a powerful tool for prevention. In fact, in most northern communities that VWB visits, the team visits schools to teach young people about the importance of recognizing and mitigating dog bites.

Challenges in the North

In many northern and remote communities, several systemic issues increase the likelihood and severity of dog bites:

- Limited access to veterinary care: This can lead to higher numbers of unvaccinated or sick dogs.

- Lack of animal control infrastructure: Free-roaming dogs may not be neutered, vaccinated, or socialized.

- Barriers to knowledge: Residents may not have access to resources on dog behaviour and safety.

PHOTO: A VWB veterinary volunteer preparing a vaccine.

PHOTO: A VWB veterinary volunteer preparing a vaccine.

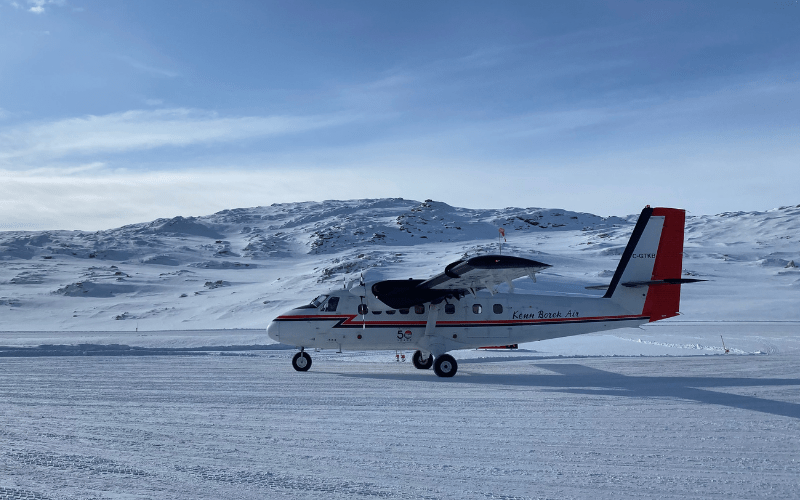

PHOTO: A flight carrying the VWB team to a remote community.

PHOTO: A flight carrying the VWB team to a remote community.

PHOTO: VWB team teaching students about animal health and dog safety.

PHOTO: VWB team teaching students about animal health and dog safety.

What can be done?

Preventing dog bites and protecting public health in remote northern communities requires a multi-faceted approach. This includes:

- Delivering culturally appropriate programs in schools and community centers about safe dog interaction.

- Training children and caregivers to recognize canine body language.

- Increased access to spay/neuter and vaccination clinics.

- Supporting initiatives that offer mobile veterinary services in remote areas.

- Providing resources on pet ownership, including nutrition, training, and health care.

- Promoting leashing and supervised outdoor time to reduce interactions between dogs and unfamiliar people

- Collaborate with Indigenous leaders, health organizations, and animal welfare NGOs to build sustainable, community-led solutions.

A safer, healthier future

Dog bites are preventable. By investing in education, access to care, and community empowerment, we can protect both people and animals from harm. This Dog Bite Prevention Week, let’s remember that preventing bites isn’t just about safety—it’s a matter of public health, animal welfare, and community resilience, especially in the North.

Join us in strengthening veterinary services worldwide! Healthier animals lead to stronger farms, more resilient communities, and a safer, more sustainable future. Donate, volunteer, or subscribe to support disease prevention, protect farmers’ livelihoods, and reinforce the vital connection between animal, human, and environmental health.

Join us in strengthening veterinary services worldwide! Healthier animals lead to stronger farms, more resilient communities, and a safer, more sustainable future. Donate, volunteer, or subscribe to support disease prevention, protect farmers’ livelihoods, and reinforce the vital connection between animal, human, and environmental health.